The Battery Shipment That Never Left the Warehouse

The Battery Shipment That Never Left the Warehouse

The pallets were wrapped.

The paperwork was ready.

The truck was booked.

And then the shipment stopped, before the batteries were ever cleared to be loaded onto the aircraft.

Nothing was wrong with the batteries themselves. They powered devices exactly as designed. They had already been sold. In some cases, they were already installed in finished products waiting to ship.

The problem wasn’t performance.

It wasn’t quality.

It was transport compliance.

For many manufacturers, this is the moment they discover that batteries are regulated very differently once they leave the factory.

When Batteries Become a Transport Risk

Lithium batteries are not treated like most other components during shipping. Once they enter the transportation system; by air, sea, rail, or road, they are classified as dangerous goods.

That classification has nothing to do with whether a battery works. It exists because of what can happen under transport conditions: pressure changes, vibration, impact, short circuits, or thermal stress.

This is where UN 38.3 comes in.

UN 38.3 testing is not about how a battery performs in a device. It is about whether that battery can safely withstand the conditions it will encounter while being transported around the world. If that evidence isn’t available or isn’t current, shipments can be delayed, rejected, or stopped entirely.

Why This Catches Manufacturers Off Guard

Most battery-related compliance conversations focus on the end product: the device, system, or equipment the battery is installed in. Transport is often treated as an afterthought, something logistics will “handle later.”

But logistics teams can’t fix missing compliance.

UN 38.3 applies not only to standalone batteries, but also to batteries:

• Installed in equipment

• Packed with equipment

• Shipped as samples, prototypes, or replacements

UN/DOT 38.3 is especially enforced by regulators when it comes to air transportation and it applies regardless of whether the battery is being shipped for the first time or the hundredth.

This is why shipments are often stopped at the worst possible moment, when production is complete and deadlines are already in motion.

What UN 38.3 Is Actually Looking For

UN 38.3 testing evaluates how batteries behave under stresses that are common in transport but rarely considered during product design.

These include conditions such as altitude changes, thermal exposure, vibration, shock, external short circuits, overcharge scenarios, and forced discharge. The goal isn’t to prove that a battery is flawless, it’s to demonstrate that it won’t create an unacceptable risk during shipping.

Just as importantly, the testing must be properly documented. Without the correct test summary and traceability, even a tested battery can face transport issues.

Where Manufacturers Can Get Tripped Up

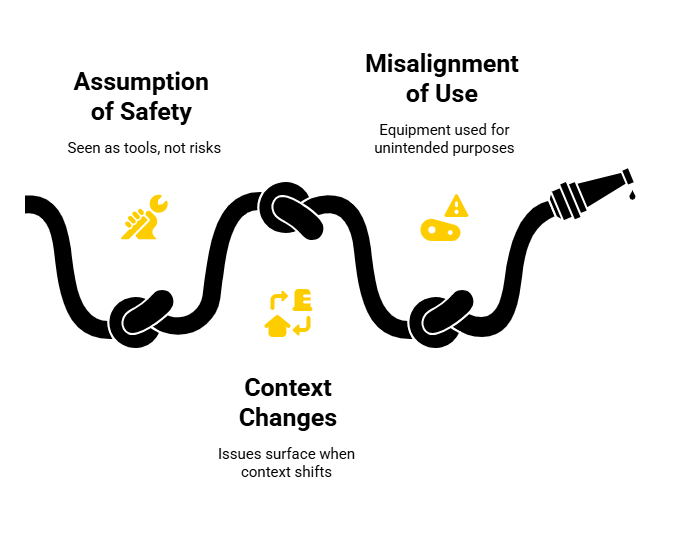

Problems often arise when:

- A battery design changes, but transport testing isn’t revisited

- A new supplier is introduced without updated documentation

- A battery previously shipped domestically is now being exported

- Prototype or low-volume shipments are assumed to be “exceptions”

In reality, transport rules don’t care about intent or volume. They care about evidence.

Where Independent Testing Actually Makes a Difference

This is usually the point where battery compliance stops being theoretical.

LabTest Certification works with manufacturers to support UN 38.3 testing and documentation so battery products can move through the transport chain without last-minute disruption. Just as importantly, we help manufacturers understand when re-testing or updated evaluation is required, and when existing evidence is still valid.

The objective isn’t to slow products down. It’s to prevent them from being stopped after everything else is already finished.

The Takeaway

Battery compliance doesn’t start when a product is powered on.

It starts when that product is boxed, labeled, and handed to a carrier.

Manufacturers who plan for transport requirements early rarely think about UN 38.3 again. Those who don’t usually meet it at the warehouse door, under pressure, on someone else’s timeline.

And by then, the shipment is no longer just a shipment.

It’s a problem waiting to be solved.