Fire Pits: Designed for Heat. Tested by Wind.

Fire Pits: Designed for Heat. Tested by Wind.

Outdoor fire pits are designed to live where control is weakest.

Unlike indoor appliances, they operate without walls, without consistent airflow, and without predictable thermal behavior. They’re exposed to shifting wind vectors, rapid pressure changes, moisture intrusion, and user behavior that can’t be scripted. And it’s under those conditions, not calm ones that performance is defined.

Most people assume heat is the dominant challenge for fire pits.

In reality, wind is.

Wind Changes Combustion, Not Just Flame Shape

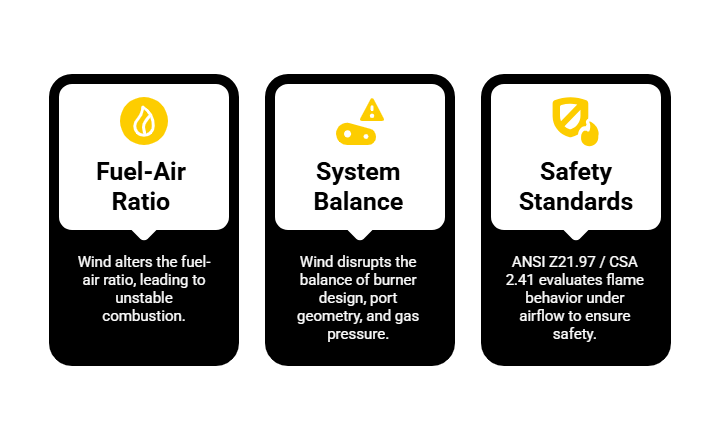

From a combustion standpoint, wind alters the fuel-air ratio in ways that static testing never reveals. Gusts can lean flames, stretch them beyond burner ports, or momentarily separate flame fronts from their fuel source. When that happens, combustion becomes unstable even if gas supply remains constant.

This matters because modern outdoor fire pits are engineered as systems. Burner design, port geometry, gas pressure regulation, and ignition methods are all tuned for predictable behavior. Wind disrupts that balance sometimes subtly, sometimes immediately.

Under ANSI Z21.97 / CSA 2.41, appliances are evaluated to ensure that flame behavior under airflow does not lead to unsafe operation, unintended extinguishing, or delayed ignition scenarios. These are not theoretical concerns, they are real failure modes observed when outdoor appliances meet uncontrolled airflow.

Heat Moves Differently Once Wind Is Involved

Wind doesn’t just affect flame stability; it redirects heat.

Testing shows that airflow can push radiant and convective heat back toward surfaces not originally intended to receive it. Control housings, valve assemblies, ignition components, and user-accessible areas may experience temperature rise patterns that don’t appear in still air conditions.

That’s why temperature limits and material selection are evaluated as part of system behavior not as isolated components. A surface that passes thermal limits indoors may exceed them outdoors once airflow reflects heat unpredictably.

This is one of the reasons outdoor decorative gas appliances are assessed as complete assemblies rather than modular parts.

Safety Systems Are Only as Predictable as Their Environment

Modern fire pits rely on safety mechanisms that assume consistent feedback: flame sensing, ignition confirmation, and controlled shutoff behavior. Wind introduces variability into those signals.

In testing, this shows up as:

- delayed ignition response

- nuisance shutdowns

- inconsistent flame sensing

- or intermittent cycling that appears random to the user

These behaviors aren’t always failures but they indicate designs that are sensitive to environmental disturbance. Standards like ANSI Z21.97 / CSA 2.41 are structured to identify whether systems remainpredictable when airflow, pressure, and exposure fluctuate.

Predictability is the real safety metric.

Rain Isn’t Separate from Wind, It’s Part of the Same Problem

Outdoor fire pits aren’t evaluated for dry conditions alone. Rain exposure is part of performance testing because moisture and airflow interact.

Water intrusion doesn’t need to be dramatic to matter. Even small amounts of moisture can influence ignition reliability, gas flow stability, and component durability when combined with wind-driven movement. Testing accounts for how appliances behave when combustion, airflow, and moisture are present simultaneously not sequentially.

Why Outdoor Fire Pit Testing Is Different

What separates outdoor fire pit evaluation from indoor appliance testing is that environmental forces are treated as active variables, not background conditions.

Certification under standards like ANSI Z21.97 / CSA 2.41 reflects:

- how combustion behaves under airflow

- how heat migrates under wind influence

- how systems respond when inputs are inconsistent

- and whether safety mechanisms act reliably without ideal conditions

It’s not about whether the flame looks good. It’s about whether the appliance behaves responsibly when the environment stops cooperating.

The Real Takeaway

Outdoor fire pits don’t fail because they get hot. They fail when wind, heat, gas, and control systems interact in ways the design didn’t anticipate; quietly, gradually, and often long before anything looks wrong.

That’s why wind isn’t a secondary consideration. It’s the real test.

And it’s why outdoor appliances are evaluated as systems not components before they’re trusted in the environments they’re built for.